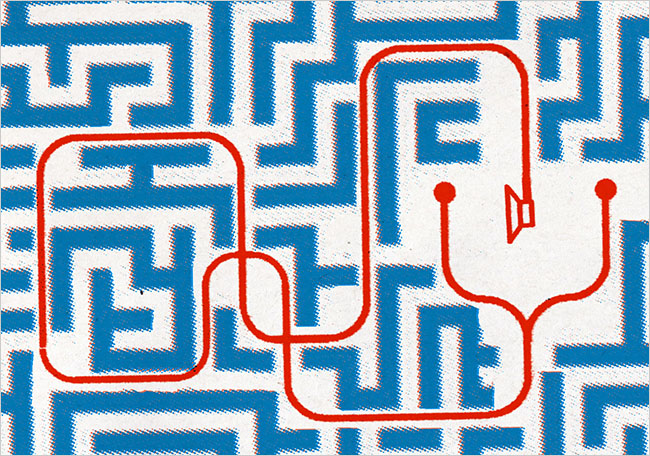

Every year medical journals publish thousands of new research studies, and few doctors have the time or expertise to read them all. To help them, a patchwork of private and public organizations distill these studies into up-to-date clinical guidelines, which are recipes that doctors follow to treat everything from ingrown toenails to heart attacks.

By creating national standards of care, these groups exert great influence over medical practice. Yet the process for creating guidelines can be idiosyncratic and error-prone, especially in regard to children’s health, leading to sudden shifts that confuse doctors and parents.

Over the last year, for example, the American Academy of Pediatrics abruptly reversed its recommendation that healthy infants avoid peanuts and other potential food allergens, without citing any new data. Weeks after the American Heart Association widely publicized the need to perform cardiac testing in children treated with drugs for attention problems, the academy issued a contradictory guideline discouraging such testing.

Last summer, the academy issued a controversial policy statement calling on doctors to check blood cholesterol levels in millions of young children and, in some cases, prescribe chronic drugs to lower cholesterol.

Dr. Roger Suchyta, the academy’s associate executive director, told me the policy was reviewed by 14 committees and the board of directors before publication. But he added that academy standards did not require any systematic overview of the scientific literature before a policy was issued. The policies may thus rely greatly on some doctors’ personal views, not clear data.

In an oversight, the cholesterol policy was not assessed by the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology, which also issue guidelines. “Nobody thought to do that,” Dr. Suchyta said.

The committee that drafted the policy also had severe time constraints, said one of its members, Dr. Jatinder Bhatia, a neonatologist in Georgia. The panel must review its policies every five years, and this year it had to consider “a whole bunch of reports,” he told me, including complex policies on infant formula and vitamin supplementation — 1,178 pages in all, of which the cholesterol policy was only 11 pages.

The committee also did not grade the quality of the evidence behind its recommendations, like beginning cholesterol tests in many toddlers as young as 2 and treating children as young as 8 with cholesterol-lowering medications.

Clinical guidelines were first developed in the 1980s, when Medicare officials asked experts to determine the appropriate use of pacemakers, which were a new, expensive technology. “From that effort, the whole concept of guideline development took off,” said Dr. Elliott M. Antman, a past chairman of the American Heart Association’s guideline development team, which wrote these first guidelines.

To produce its recent guidelines on heart attack treatment, he estimated, the group spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to review and grade clinical evidence and to assemble a team of dozens of experts. Few organizations invest these resources into creating guidelines.

A report in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that only about a third of clinical guidelines reviewed current medical evidence. Fewer than half followed any kind of standard format.

Dr. Suchyta says the only group that finances comprehensive reviews of pediatric health evidence is the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. So far, though, it has sponsored only about a dozen independent reviews, which serve as the basis of reliable clinical guidelines.

Despite this evidence gap, the pediatrics academy has released hundreds of care recommendations. The academy is a leading contributor to the National Guideline Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov), a public database created by the American Medical Association that contains the consolidated wisdom of American medicine in more than 2,200 guidelines. Among domestic contributors, the academy is topped only by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Radiology.

Many of the academy’s recommendations — on topics as diverse as breast feeding, circumcision and learning disabilities — may arouse controversy. Moreover, they may lead to jarring shifts over time, because the evidence is not explicitly rated for quality.

By contrast, the United States Preventive Services Task Force clearly scores its guidelines. Routinely checking blood pressure is a Grade A1 practice (highly recommended, with good evidence), while routine mammography gets a B2 (less strongly recommended, with fair evidence).

Evidence-based guidelines are critical to protecting public health from bad medicine. In a notorious 2006 example, a group of cardiologists in Texas published its own guideline promoting routine, and expensive, cardiac CT scans in healthy middle-aged people. The guideline, which lacked any evidence grading, appeared in a supplement to The American Journal of Cardiology financed by Pfizer, which makes the cholesterol-lowering drug Lipitor.

Peter Jacobson, a health law professor at the University of Michigan who investigated the rogue guideline, told me he “never got a straight answer as to whether it was submitted for peer review.” The guideline also failed to disclose any author conflicts of interest. Fortunately, because more trusted groups like the heart association had more explicit evidence-based guidelines, the rogue guideline failed to gain wide acceptance.

In contrast, because most pediatric guidelines lack evidence standards, doctors have trouble knowing which ones are reliable. Last year, the International Society for Bipolar Disorders released a guideline to diagnose bipolar disorder in children, and the lead author reported financial ties to seven manufacturers of psychiatric medications. No clinical evidence was cited in the guideline. Because the American Academy of Pediatrics lacks better evidence-based guidelines, this could become the standard of care.

Given the background noise from poor guidelines, some doctors ignore even high-quality ones. For example, fewer than one in three pediatricians follow the pediatrics academy’s guideline on ear infections, which discourages overuse of antibiotics. That sensible recommendation arose from a comprehensive federal review of evidence.

In standardizing care through pay-for-performance incentives, large insurers like Medicare may increasingly reward doctors for following clinical guidelines. Before that happens, though, it will be critical to establish better standards for the standards — especially for children.